- Posted on

- Craig Gundry

- 0

Ten Steps to Managing Risks of Active Shooter Violence in Schools

Managing risks of active shooter violence in schools requires effective integration of policies and preparations in terms of school infrastructure, physical security, life safety design, and faculty training. The following ten points summarize some key security and preparation measures for protecting schools during active shooter events.

1. Implementing a Student Threat Assessment System (STAS).

Many acts of school violence by juvenile perpetrators are precipitated by communications or behavior that, if properly recognized and assessed, can indicate a potential threat of targeted violence. Considering the frequency of school shootings by student perpetrators (over 59%), implementing a formal system for recognizing, reporting, and assessing threatening behavior is a crucial first line of defense against active shooter attacks.

In response to the school shootings of the 1990’s (which were by percentage overwhelmingly committed by students), the US Secret Service and National Center for the Analysis of Violent Crime (NCAVC) initiated a program in 2001 to study the perpetrators of targeted violence in schools and dynamics of escalation in an effort to design a strategy that schools could employ for use in identifying and managing threats before they escalate into violence. The product of this study was the Safe School Threat Assessment guidelines published in 2002.[1] [2] Over the past two decades, researchers have added further to the body of research on targeted violence in schools providing a rich foundation of knowledge to aid in the challenging process of discerning genuine threat situations from benign circumstances.[3]

A number of models and methodologies have been designed for use by schools in assessing and managing threat situations. Some examples include the Comprehensive School Threat Assessment Guidelines (CSTAG), Salem-Keizer STAS model, and MOSAIC for Assessment of Student Threats (MAST).

In addition to adopting an effective model for threat assessment, effectively implementing an STAS program requires training STAS team members in important aspects of targeted violence psychology and assessment methodology in addition to educating teachers on how to recognize and report threat communications and warning behaviors.

2. Concealment/obscuration of students located outdoors or adjacent to windowed areas to reduce risk of surprise attack from outdoor locations.

A noteworthy percentage of active shooter attacks by outsider adversaries commence against people located outdoors (and subsequently progress indoors) or are launched from outdoor locations against people visibly located in indoor areas. Some recent examples of attacks launched outdoors include assaults at the Ozar Hatorah School (Toulouse, 2012), Route 91 Harvest Festival (Las Vegas, 2017), Eugene Simpson Stadium Park (Alexandria, 2017), Curtis Culwell Center (Gardland, 2015), Inland Regional Center (San Bernardino, 2015), Charlie Hebdo office (Paris, 2015), and Overland Park Jewish Community Center (Kansas City, 2014).

The primary countermeasure against surprise outdoor attack scenarios is obstructing sightlines of student congregated in outdoor recreation and assembly areas from publicly accessible locations around the perimeter. Additional preparations include providing multiple options for rapid egress and dispersal from outdoor areas and use of automated systems for detecting outdoor shooting events to expedite alert and response.

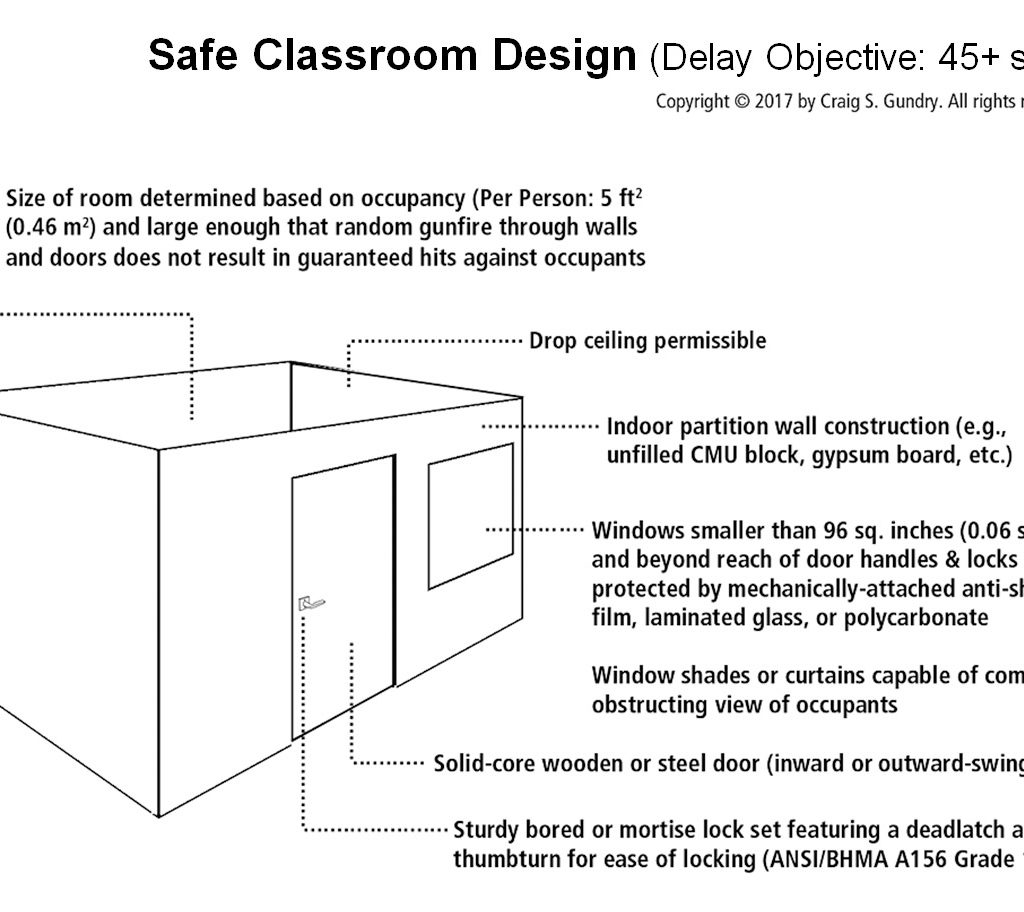

3. Delay the attacker’s ingress into student-populated areas to permit time for critical alerts, escape and refuge actions, and deployment of an armed response force.

Campus security design should incorporate layers of intrusion-resistant barriers to delay an attacker’s movement into areas populated by students. If the attacker is an ‘outsider,’ this includes exterior barrier layers (e.g., facade glazing, doors, locks, etc.) and delay measures inside unsecured lobbies. Additional protective layers securing classrooms should be used to frustrate adversary ingress further and provide critical delay against movement by ‘insider’ adversaries (e.g., student gunmen, etc.) already located inside the school building.

For purposes of barrier construction and performance during active shooter events, the most important barriers are glazing, doors, and locks. In a large percentage of attacks, adversaries focus on targets of easiest opportunity by using visually-obvious pathways and unlocked/unobstructed portals (e.g., doors, windows, etc.) to facilitate indoor movement.[4]

4. Early detection and assessment of the threat.

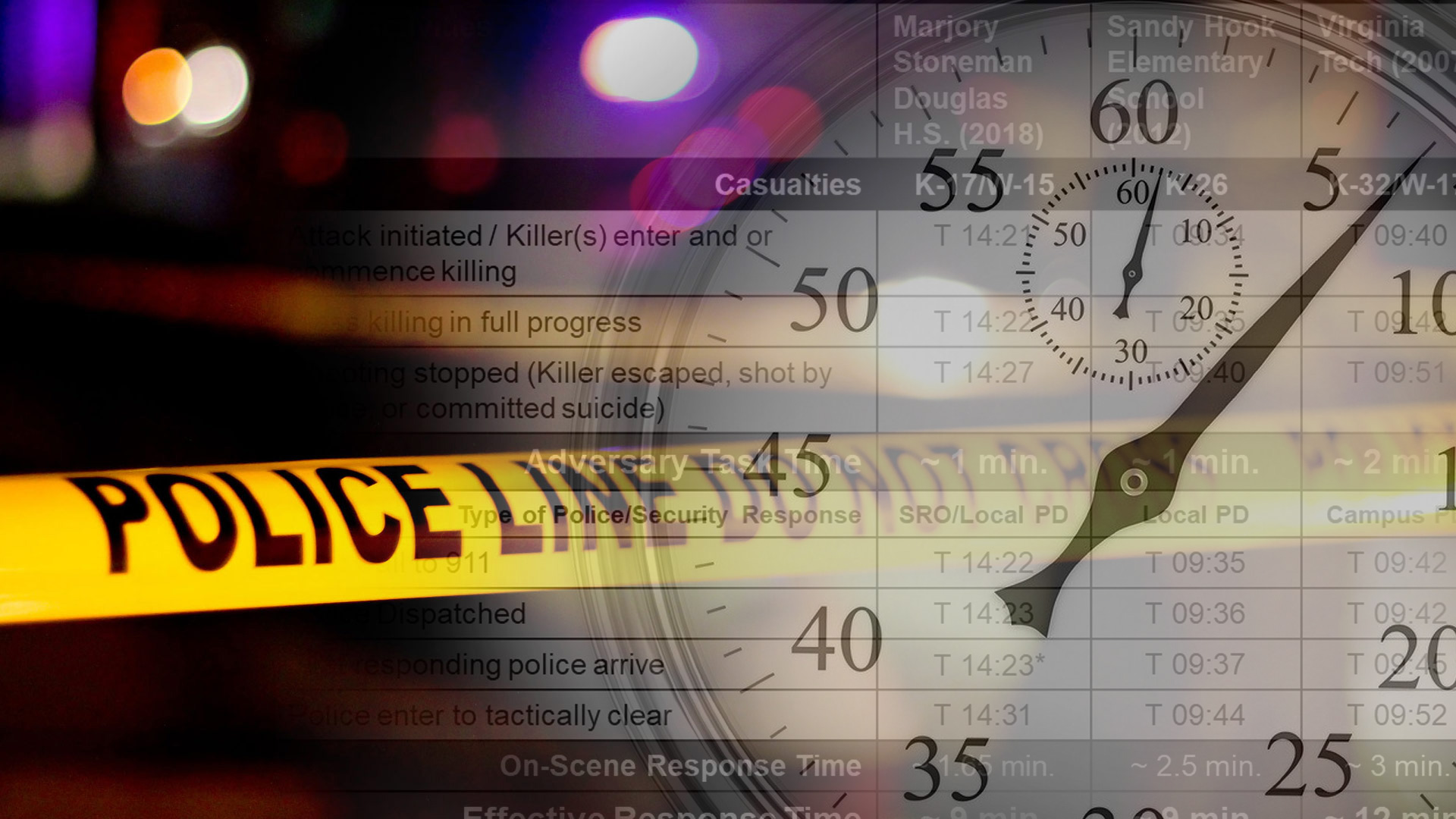

In active shooter incidents, time is critical and every measure that expedites detection of the attack and deployment of an armed response force is important in mitigating the consequences of an event. As part of the incident data collection process during Purdue University’s 2014 Mitigating Active Shooter Impact study, researchers collected information about response times and casualties related to 24 school shootings and 41 workplace shootings in the United States. The Purdue report describes: “The average time in shooting events ranged from 3 to 4 minutes with an average victim being shot every 15 seconds.”[5]

Measures that expedite event notification to security or authorities, such as panic alarms, can greatly reduce the typical detection times normally encountered by relying on witnesses to call an emergency number by telephone. Even better time performance can be achieved with the use of gunshot detection sensors. Gunshot detection sensors also automate detection and reduce the possibility of delayed notification if a person responsible for panic alarm notification is disabled or away from their station.

5. Rapid and reliable alert communications.

A critical part of effective response during active shooter events is fast and reliable mass notification alert to expedite protective actions by students and faculty. Critical alerts should always be issued by audible means (public address) for the benefit of all school occupants and accompanied by a redundant message via mass notification system (MNS) for those who may not have heard the initial announcement. When important developments occur, updates can be issued to faculty as follow up messages. Circumstances warranting updates may include notification when police are clearing the school or if a unique threat emerges, such as a building fire.

To facilitate rapid audible alerts, school administrators should have fast and reliable access to the school’s public address system from anywhere on campus. If the school does not have a phone or paging system capable of providing this level of versatility, body-worn alert devices capable of emitting audible alert messages (such as GuardianCall) can ensure fast and reliable delivery of key notifications.

Mass notification systems should also be easy to use under stress and optimally feature pre-configured messages for key alerts to minimize the time required to type and send messages.

6. Simple and rapid evacuation/escape by faculty and students.

For older students located at ground level or in locations without safe refuge options, escape (DHS’ term ‘Run’) is the primary response. Easy to locate escape routes should be available that permit fast and unobstructed egress to safe outdoor locations away from the school.

Although all buildings are required to comply with life safety codes related to emergency egress, NFPA and municipal building codes generally fall short in considering the unique dynamics of evacuation during armed events and do not account for issues such as sympathetic nervous system (SNS) impairment of evacuees, mobile adversaries, and lack of situational awareness that may render a large number of exit routes unsafe or at least perceived as potentially-dangerous by evacuees. Optimal school design provides multiple escape options by providing access to alternative exits and easily navigated egress paths.

In active shooter attacks against multi-floor facilities, the main floor is often where the attack originates and may be a dangerous location while an event is active. If building occupants are not aware of the exact location of the threat, the combined effect of fear and lack of situational awareness may make people hesitant to evacuate if they need to pass through interior areas on lower levels to access building exits. This issue may be compounded further by the effects of the SNS on problem-solving ability. To address these issues, emergency exit stairwells from upper building levels should ideally discharge through exit doors directly to outdoor areas at ground-level. Stairwells that discharge into first floor hallways or lobbies should be strictly avoided.

Good preparation for active shooter events also considers the fail-safe or fail-secure function of doors equipped with electrified locking systems. International Building Code and NFPA codes dictate that egress doors equipped with electromagnetic locks fail-safe (unlocked) automatically when a fire alarm is activated.[6] However, during an active shooter event, doors equipped with electromagnetic locks that cannot be opened rapidly by evacuees can delay escape from the building and create dangerous congestion at exit doors. Conversely, interior doors secured by electrified locks programmed unnecessarily to fail-safe during fire alarms can compromise security during armed attack events. If a fire occurs during an attack (e.g., 2008 Taj Majal Hotel Mumbai) or someone activates a fire pull station handle (e.g., 2013 Washington Navy Yard, 2015 Corinthia Hotel Tripoli, etc.) access-controlled locks that automatically fail-safe can easily compromise any delay benefit provided by inner protective layers.

Lastly, exit signage should be clearly visible from all hallways and direct evacuees to the most accessible stairwells or egress routes.

7. Availability of safe refuge options for staff and students unable to safely evacuate or who are unaware of the threat’s location.

One of the most basic facility preparations is ensuring adequate availability of intrusion-resistant classrooms for students to take refuge if escape is not feasible. For this purpose, classrooms which meet essential safe room criteria should be abundantly available capable of providing adequate delay against forced entry considering the methods and tools likely to be employed by attackers.

Optimal safe room designs specify delay time objectives based on the expected effective response time of police or on-site security forces. However, in the United States where most active shooter events are resolved in less than 10 minutes, simply providing enough delay to frustrate adversary attempts to gain entry is often a justifiable and practical compromise. Joseph Smith and Daniel Renfroe describe their observations on this matter in an article on the World Building Design Guide web site: “Analysis of footage from actual active shooter events have shown that the shooter will likely not spend significant time trying to get through a particular door if it is locked or blocked. Rather they move to their next target. They know law enforcement is on its way and that time is limited.”[7]

Separate case research conducted by Critical Intervention Services also supports Smith and Renfroe’s perspective.[8]

To frustrate adversary attempts to enter rooms where students are taking refuge, a basic-level safe classroom should provide at least 45 seconds of delay against a gunman using primarily firearm projectile penetration and impact force as the means of entry.

Safe classrooms should be abundantly available throughout the school and especially on upper building levels where egress through stairwells may require staff or students to move past potentially dangerous lower-level floors.

8. Ability to monitor attacker movement during an attack and relay critical information to emergency responders.

If a school or school district has a security operations center responsible for monitoring CCTV cameras or a CCTV system is capable of remote access, surveillance cameras can provide valuable real-time information about the adversary’s movement and activity. Any activity or technology that aids in locating the attacker and expedites intervention by police or armed security personnel can have a huge impact in mitigating consequences. Observation of the adversary’s actions can also provide critical information about developing threat situations (such as an adversary setting fire inside the building or forcibly entering rooms) that should be relayed as warning to faculty.

During the 2008 attack at the Taj Mahal Hotel in Mumbai, security officers and police located inside the hotel’s security control room were able to monitor the actions of terrorists by CCTV and relay information to outside police commanders for several hours until fire endangered their position. In the 2015 assault at the Corinthia Hotel Tripoli, the control room remained operational throughout the entire event.[9] Two security officers posted in a sublevel control room were able to track the terrorists’ movements by camera and relay valuable updates to hotel guests and Libyan security forces. Information provided by the control room even enabled the former Libyan Prime Minister’s security detail to evacuate their principal down a safe stairwell as the attackers were advancing upward through a different staircase.[10]

During attacks in large and complex school facilities, live CCTV tracking capability is invaluable. Without real-time information about an attacker’s location, police searching for an attacker in a large and unfamiliar building environment are at a great disadvantage. As an example, during the 2013 attack at Washington Navy Yard Building 197, NCIS agents and D.C. Metropolitan Police officers spent 31 minutes searching the building before locating Aaron Alexis.[11] In the D.C. Metro Police Department’s After Action Report (AAR), the size of the building and its complex layout was described as one of the largest challenges affecting their response.

To be effective in this application, CCTV systems should provide coverage of locations along likely adversary movement paths (e.g., entrances/exits, lobbies, stairwells, hallways, etc.) and be easily navigated by control room personnel under high stress conditions.

9. Rapid deployment of a response force capable of neutralizing an armed attacker.

Although many active shooter attacks terminate in suicide before the intervention of police or security forces, the speed at which security or police arrive and locate the adversary has a direct impact on consequences of the event.

In an FBI-published analysis of 51 active shooter events in the US between 2000 and 2012 where data on response times was available, police response times ranged between 0-15 minutes with a median response time of 3 minutes.[12] However, this analysis does not necessarily describe the true Effective Response Time. The Effective Response Time is defined as the total time from commencement of the attack and subsequent emergency notification to the time that security or police forces located and neutralized the perpetrator. For example, at Sandy Hook Elementary School, police officers arrived on scene at 09:37 (~2.5 minutes after the first 911 call and only 3-4 minutes after Adam Lanza opened fire). However, officers did not tactically clear the building and arrive at Lanza’s location until 09:44 (~4 minutes after Lanza committed suicide).[13] In many incidents we have case studied over the past several years, the police dispatch and arrival times aligned with the findings of the FBI analysis but there was at least an additional 2-5 minutes of time before officers made entry and located the attacker.[14] In larger or more complex facilities, effective response times could be much longer.

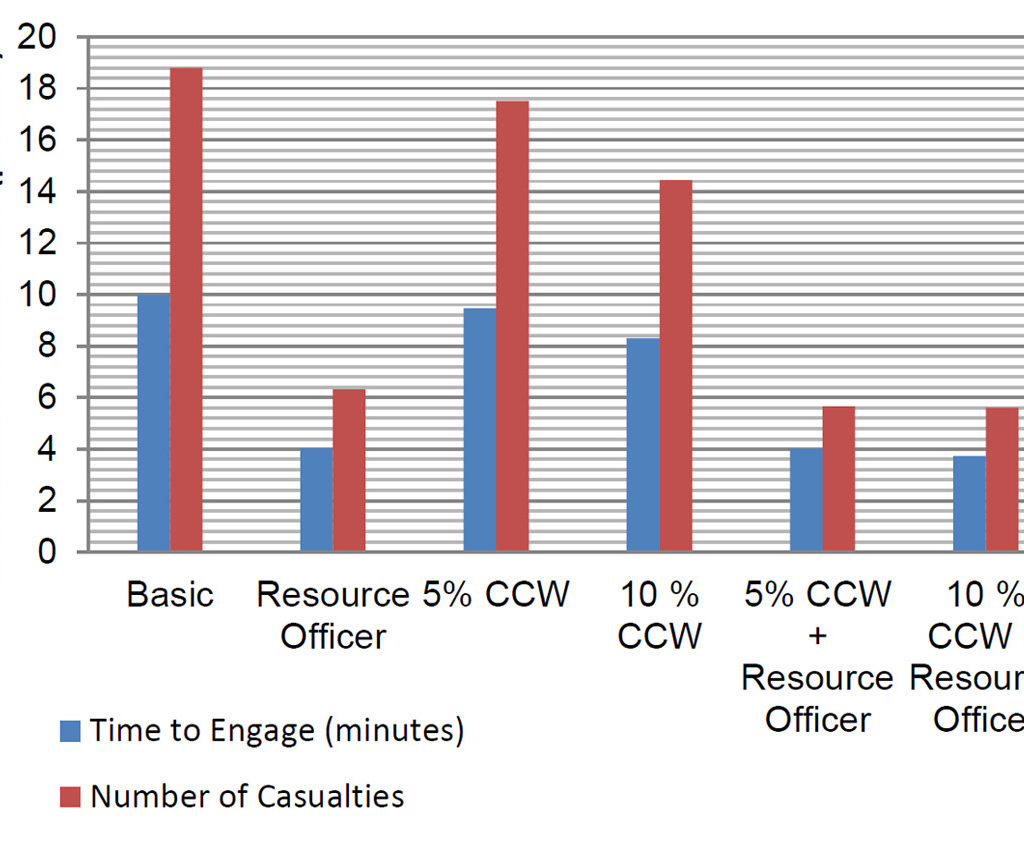

In 2014, Purdue University researchers conducted a study using agent/computer-based modeling to assess the potential effectiveness of several different response scenarios during active shooter attacks. The scenarios evaluated included Basic (off-site police dispatched in response to 911 calls), Resource Officer (on-site police or armed security), and four variations involving concealed carry weapon holders amongst the population of school employees.

As indicated in the chart below, the results of the Purdue University study were very conclusive. Although the results deviated slightly for scenarios involving concealed weapon holders among the faculty population, the greatest factor impacting both response time and casualties was the presence of a School Resource Officer on campus.[15]

Although having an on-site armed response capability can greatly mitigate the consequences of active shooter events, implementing this measure requires consideration of cost, training, location assignment, and liability.[16] Implementation in a previously unarmed school also requires careful planning to ensure the integration of armed officers into the environment and acceptance by students, parents, and faculty.

If a school cannot implement an on-site armed response capability, additional measures should be used to expedite the effective response of local police. Some examples of preparatory measures include distinctive marking of buildings on multi-building campuses to ease location, establishing procedures for coordinating and directing arriving law enforcement officers, and preparations for providing building keys, access control badges, and floor plans to facilitate unimpeded movement indoors by police.

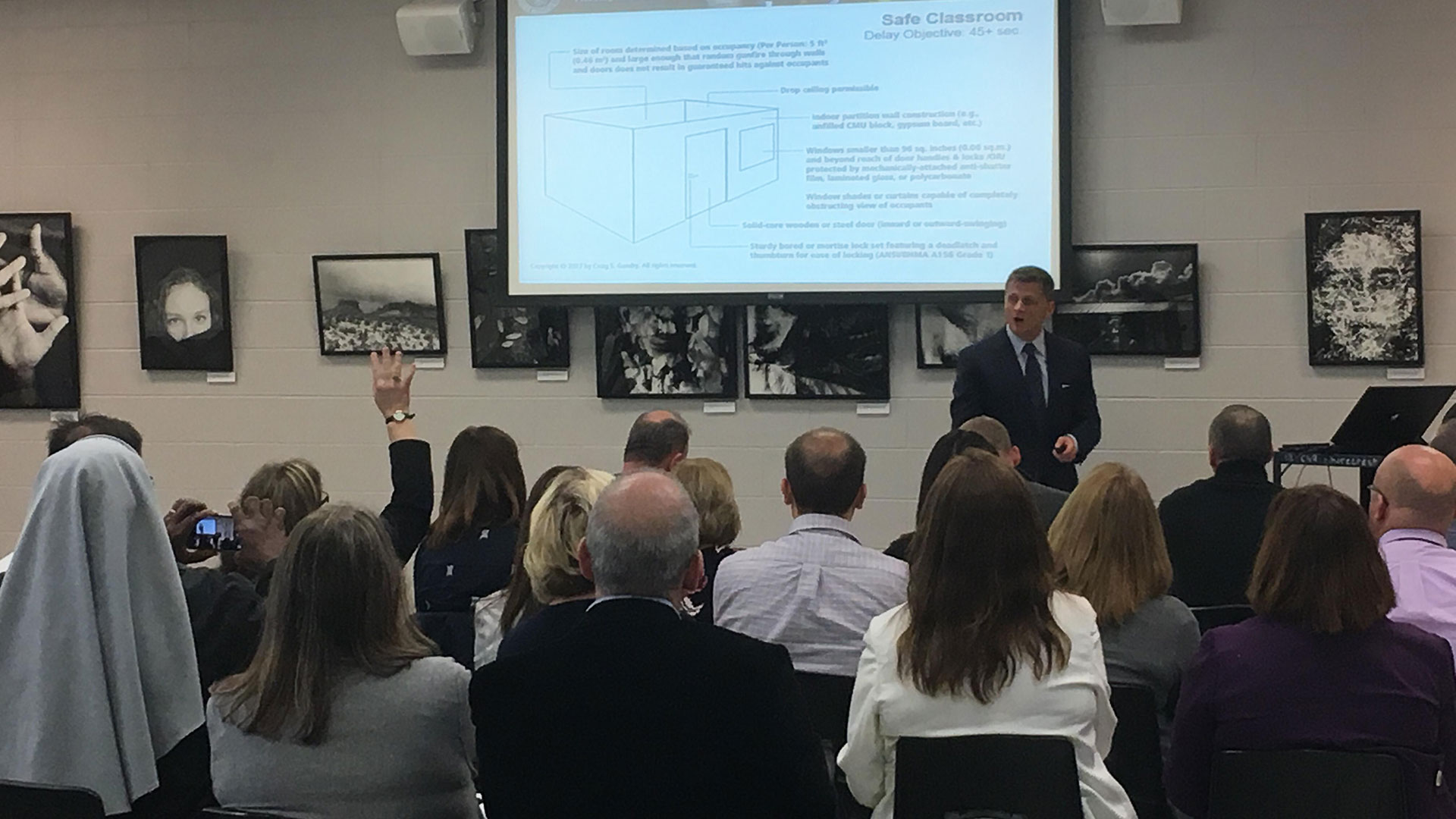

10. Training faculty and students in safe response actions.

Even the best designed plans and facility preparations will fail if school employees are unprepared to take action for their self-preservation and protection of students during active shooter events. As described elsewhere in this essay, the combined effects of the sympathetic nervous system during high stress events and lack of situational awareness can have a debilitating effect on people’s response and even lead to dangerous actions. The first step in combating this problem is training staff and faculty in emergency response procedures.

It is also recommended that training be conducted annually for all staff and faculty and include instructor-led discussion about school-specific measures for contacting security or police, safe lockdown or escape procedures, special egress considerations (e.g., feasibility of roof access, campus gates, etc.), communications systems, and location of medical kits.

In addition to classroom instruction, schools should ideally conduct at least one active shooter response drill per quarter. One of our clients, Shorecrest Preparatory School, conducts lockdown drills bi-monthly to ensure that teachers and staff members are instinctive in their response. When questioned about the frequency of lockdown drills versus legally-mandated fire drills, Mike Murphy (Headmaster at Shorecrest Prep) tells people, “No children have been killed in school fires in over 50 years but one only needs to watch this week’s news to be reminded of the last time kids were killed in an act of school violence.”

[1] United States. US Secret Service & US Department of Education. Threat Assessment in Schools: A Guide to Managing Threatening Situations and to Creating Safe School Climates. Washington, D.C. May 2002. PDF.

[2] O’Toole, Mary Ellen, PhD. National Center for the Analysis of Violent Crime, FBI Academy. The School Shooter: A Threat Assessment Perspective. Quantico, VA. PDF.

[3] Meloy, J R., and Jens Hoffmann. International Handbook of Threat Assessment. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014. Print.

[4] Smith, Joseph, and Daniel Renfroe. “Active Shooter: Is There a Role for Protective Design?” World Building Design Guide, National Institute of Building Sciences, 2 Aug. 2016, www.wbdg.org/resources/active-shooter-there-role-protective-design. Accessed 22 Sept. 2017

[5] Anklam, Charles, Adam Kirby, Filipo Sharevski, and J. Eric Dietz. “Mitigating Active Shooter Impact: Analysis for Policy Options Based on Agent/computer-based Modeling.” Journal of Emergency Management 13.3 (2014): 201-16.

[6] International Code Council. International Building Code, 2012. Country Club Hills, IL: International Code Council, 2011.

[7] Smith, Joseph, and Daniel Renfroe. “Active Shooter: Is There a Role for Protective Design?” World Building Design Guide, National Institute of Building Sciences, 2 Aug. 2016, www.wbdg.org/resources/active-shooter-there-role-protective-design. Accessed 22 Sept. 2017.

[8] Gundry, Craig S. ” Safe Rooms and The Active Shooter Threat.” Web blog post. LinkedIn. N.p., 25 Sept. 2017. https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/safe-rooms-active-shooter-threat-part-one-gundry-psp-cato-chs-iii/ Accessed 23 October 2017.

[9] [CONFIDENTIAL] Incident Report. Attack at the Corinthia Hotel Tripoli. [CONFIDENTIAL SOURCE] 27 January 2015.

[10] Ibid.

[11] After Action Report. Washington Navy Yard. September 16, 2013. Internal Review of the Metropolitan Police Department of Washington, D.C. Metropolitan Police Department, Washington, D.C. July 2014.

[12] Blair, J. Pete, Martaindale, M. Hunter, and Nichols, Terry. “Active Shooter Events from 2002 to 2012.” FBI Law Enforcement Bulletin. Federal Bureau of Investigation, 1 July 2014, https://leb.fbi.gov/2014/january/active-shooter-events-from-2000-to-2012. Accessed 22 Sept. 2017.

[13] Report of the State’s Attorney for the Judicial District of Danbury on the Shootings at Sandy Hook Elementary School and 36 Yogananda Street, Newtown, Connecticut on December 14, 2012. Office Of The State’s Attorney Judicial District Of Danbury, Stephen J. Sedensky III, State’s Attorney, N.p., 25 November 2013

[14] Gundry, Craig S. Preparing for Active Shooter Events. ASIS Europe 2017, 30 Mar. 2017, Milan, Italy.

[15] Anklam, Charles, Adam Kirby, Filipo Sharevski, and J. Eric Dietz. “Mitigating Active Shooter Impact: Analysis for Policy Options Based on Agent/computer-based Modeling.” Journal of Emergency Management 13.3 (2014): 201-16.

[16] Gundry, Craig S. “Security Officer Posting and Active Shooter Attacks.” Web blog post. LinkedIn. N.p., 7 Mar. 2017. https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/security-officer-posting-active-shooter-attacks-gundry-psp-chs-iii/ Accessed 23 October 2017.